consolidating multiple team hypotheses

Client:

Department for

Work & Pensions (DWP)

Area:

Health & Disability

Role:

Senior Service Designer

The problem

Each year, DWP supports over 2 million people with disabilities and health conditions, who decide to apply for benefits / support.

As part of this process, some citizens will be required to have a functional health assessment with a qualified healthcare professional. These assessments are carried out using specific criteria set out by the Government and provide DWP with independent advice in the form of an assessment report.

DWP decision makers then review these reports, along with any supporting evidence and give a decision on entitlement.

The Health Assessment Service (HAS) was looking to transform this application and assessment process by focusing on the following key areas:

- Creation of Departmental Transformation Areas (DTA)

- Developing HAS within these areas, initially at small scale

- Iterating on ideas from claimants, stakeholders and DWP staff, via a ‘Test and Learn’ approach.

The programme was announced in March 2019 and I worked in this area for a period of 8 months between Dec 2021 – Aug 2022.

The landscape

On joining the programme, I needed to assess the landscape quickly since the first DTA had already gone live (in April 2021), and there were plans to add further sites and scale gradually towards a wider national roll out.

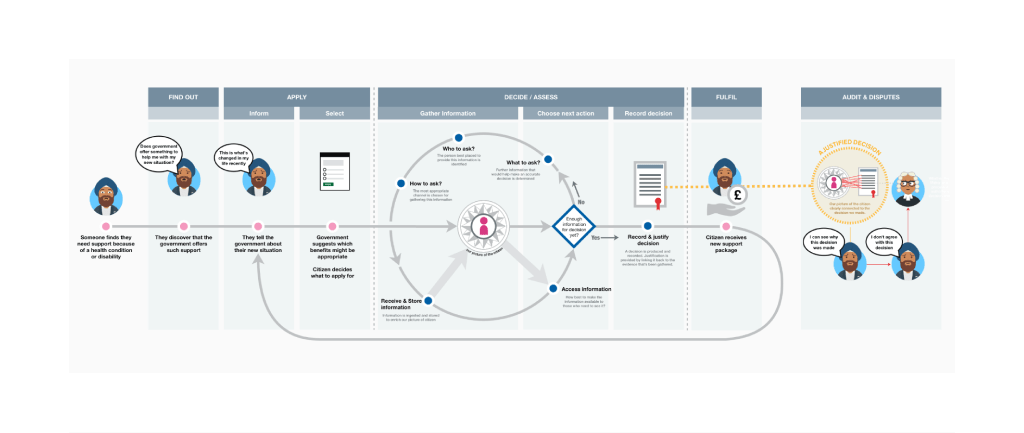

The high-level journey map I was presented with was as follows:

Whilst these stages / phases were generally well understood, what was less well defined were the hypotheses to be explored at each of these points.

That’s not to say there was an absence of hypotheses… on the contrary there was a proliferation of them.

But since they’d originated from multiple sources and disciplines over a long period of time, there was a lack of consistency in terms of style, content and purpose. It was also not always clear how these hypotheses related to the higher-level goals and outcomes that were looking to be achieved.

Coupled with this was a sliding scale of stakeholder buy-in re the merits of ‘hypotheses and experimentation’ vs ‘delivery and stabilisation’.

What did I do about it?

My primary activities were as follows:

- Gather existing hypotheses into a single digestible view

- Create a simple hypothesis framework (to manage expectations, planning and prioritisation)

- Review all of the existing hypothesis (including drafting, metrics, quality etc)

- Facilitate gap analysis (e.g. missing or insufficient hypotheses)

- Increase hypothesis buy-in and visibility across the board

How did I go about this?

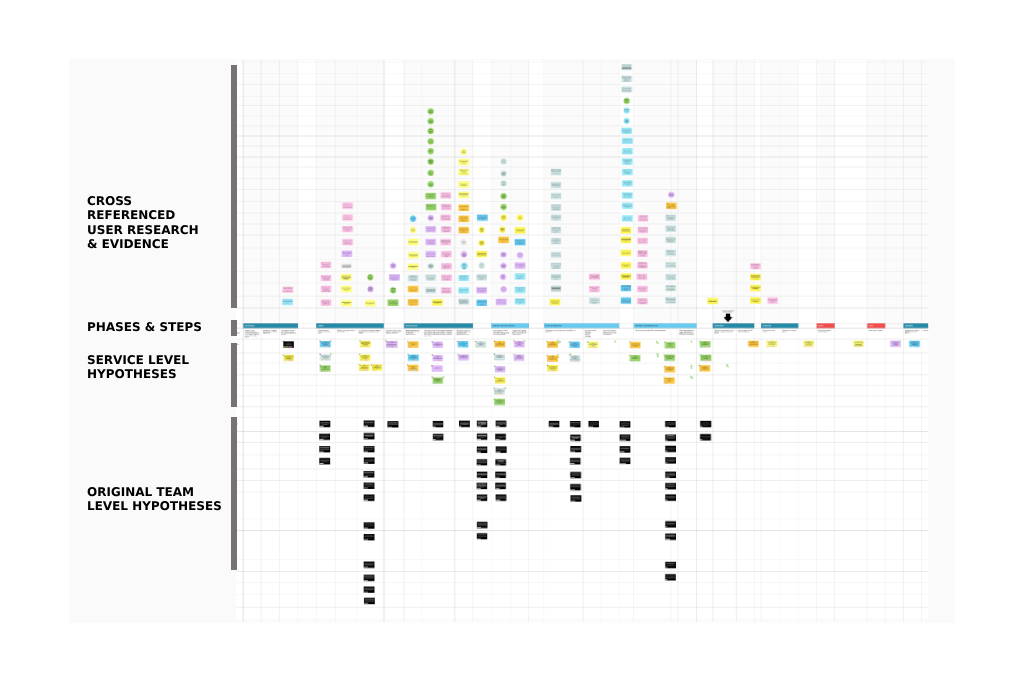

My starting point was to review an existing activity map, which for a variety of reasons, had evolved into an impregnable forest of post-it notes. A cross section of which can be seen below:

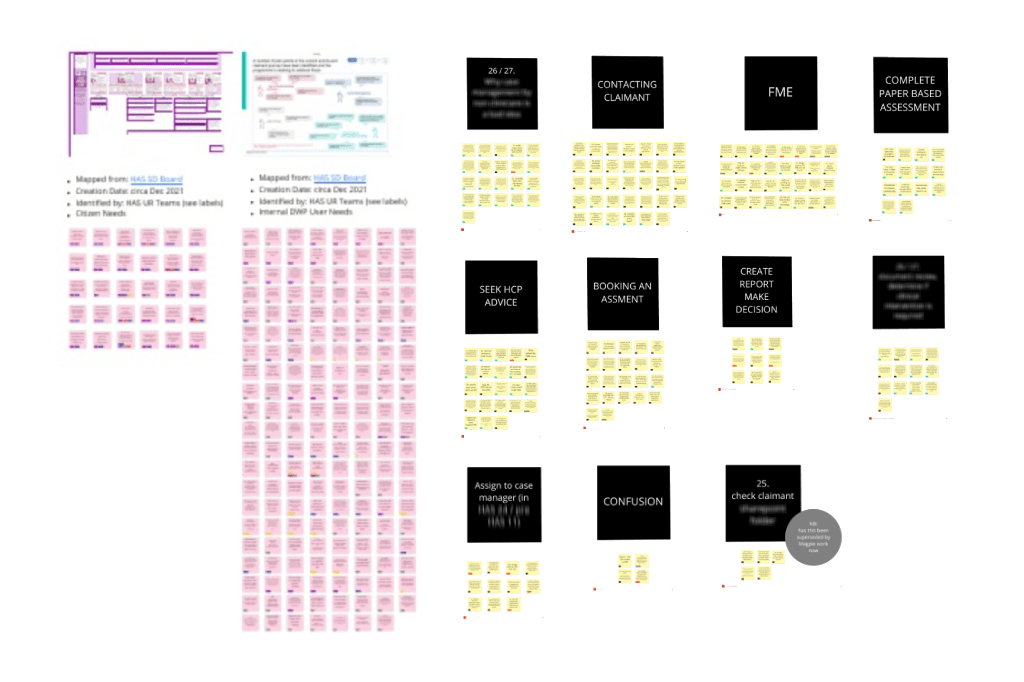

These post-its were a mixed bag of pain points, observations, manual processes, internal user wish lists and workarounds. I decided to prune back the forest through the introduction of some high-level groupings, for instance:

- Further Medical Evidence Required

- Booking an Appointment

- Creating a report

- And so on

Working closely with User Researchers, Business Analysts, Case Managers, Health Care Professionals and the Behavioural Science team. We began to define logical clusters and were able to start thinking about how these related to a Service Blueprint, rather than the more process driven Activity Map.

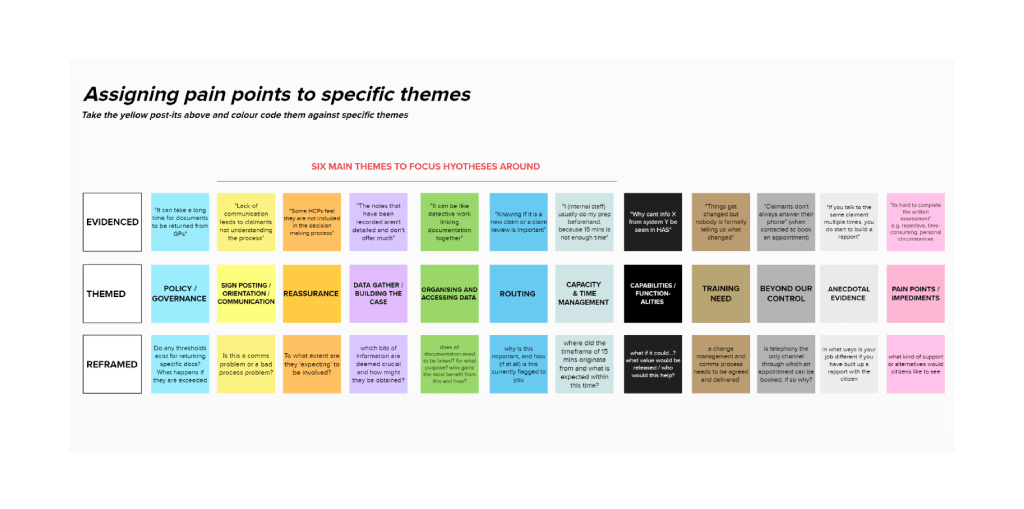

My aim was to shift thinking away from merely documenting ‘pain points’ within a process.

For example, ‘claimants not answering their phones’ (as part of an existing manual process), isn’t really the problem to be solved. It should be less about ‘how do we make people answer their phones’ and more about exploring alternative methods to secure an appointment. Hypothesising how that could be done and then validating those ideas through experimentation.

The image below demonstrates the kind of thinking I was trying to encourage. The ‘evidenced’ items are singular examples from the post-its we sanitised from the original activity map , whilst the ‘themes’ were the groupings we created to help clear the wood for the trees. The ‘re-framed’ items were the discussions under those themes I was looking to cultivate within each of the multi-disciplinary teams.

The next few images show some of the more detailed categorisations we did ahead of any re-framing.

What I found most interesting was the sheer volume of post-its that fell under the category of ‘capability / functionality’ (marked as black in the image below). But I also felt it was a big clue as to why a hypothesis led approach had failed to land so far.

In my opinion, there had been a disproportionate focus on simply going end-to-end, rather than finding the most efficient routes that delivered the most value to the user and the business.

Bringing it all together

Now that we had structured our evidence, it was time to marry it to the hypotheses that were currently being worked on, or considered at that time. I organised workshops with each of the 13 delivery teams and asked they bring their current hypotheses with them, a cross section of which can be seen below:

Repeating the same process as before, we assigned specific colours and themes to each hypothesis, before mapping them to our new high-level blueprint. We also took the opportunity to review and fine-tune as we went. Not necessarily ‘red penning’ but looking for commonality and trying to condense the original number down to something more manageable. My ultimate goal was to introduce a set of ‘service level’ hypotheses that were independent of any specific team.

An important aspect for me at this point, was to ensure the new service level hypotheses still adequately represented what had gone before. I still wanted the teams to recognise themselves in these new versions and be comfortable their work was referenced in sufficient detail. As such, no service level hypotheses were introduced until they had been collectively signed off by each team.

Keeping strategy in mind

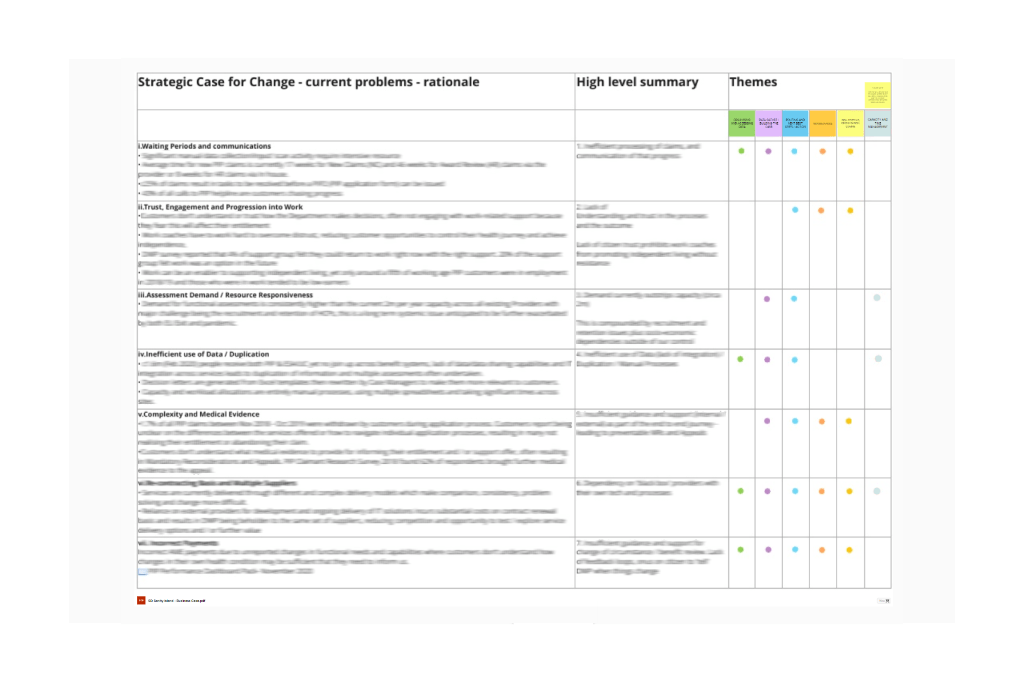

Since one of my objectives was to create and retain buy-in for a hypothesis led approach, I was keen to demonstrate how it could be aligned to artefacts such as the Target Operating Model, the Strategic Business Case and its Strategic Case for Change.

The business case contained a number of high level rationales that I wanted to use as jumping off points. However, a large proportion of these were rooted in singular pain points and singular metrics.

Typical examples would be things like

- improve claim processing time

- reduce the number of withdrawn claims

- average length of an assessment

- and so on

Unfortunately when things are framed in this way, it tends to make people focus on moving the metric as opposed to the root cause.

To ensure our hypotheses remained aligned to strategy but also retained enough breathing space for exploration, I opted for an ad hoc Hypothesis Matrix. It contained the original rationales from the business case, a plain English summary of those rationales, and which of our previously identified themes each of them fed into.

Since all of our hypotheses were colour coded to match our themes, stakeholders were able to use our blueprint to see at a glance which phases and steps were most closely related to their own strategic objectives.

The Reception

Having shifted teams focus towards a blueprint orientated approach, whilst also grounding hypotheses in traceable user research, I was confident I had achieved my goals.

Conversations with senior stakeholders also had a more structured feel to them, as sprintable work within delivery teams could now be traced back upstream to high-level outcomes.

I departed for a role in Working Age quite soon after this piece of work was delivered but felt I had left the area with a solid foundation to build from, a clear story to articulate to senior leadership and some strong recommendations for future ways of working.